Chapter 3: JULY – MORE SALMON

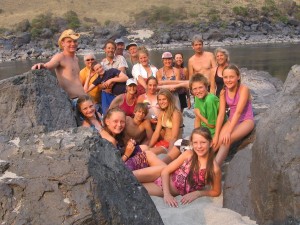

The Salmon River and my family go back decades. Before Ruby was in school we started taking yearly trips down the lower section of the river, from Hammer Bar near White Bird, Idaho to Heller Bar, on the Snake. The same Heller Bar that was our June take-out on the Grande Ronde. A group of families were in on it, and on a given July or August, the crew ranged from 15 to 25 people. The kids were more or less the same age and from the get go, the trip had everything kids love. It has big sand beaches. It has rollicking rapids. It has cliffs to jump from into deep pools. It has rapids to swim through. The weather was warm and dry, sometimes too warm. The food, catered through combined parental efforts, was plentiful and tasty. The chores and duties and discomforts were minimal. Everything about it clicked. Parents liked it too, despite the work of putting it together, getting there, managing the herd of short people. We liked it for the same reasons the kids did, even if putting the shindig on bordered on the heroic.

Various traditions and legendary stories came of those trips. Picking blackberries oblivious to thickets of poison ivy, or finding a grove of apricot trees heavy with ripe fruit in one of the camps. The dead tree sticking out over the river, twenty feet up, lodged there in some monstrous flood year, that we took turns walking the plank on and leaping into the deep water below. The kids spreading a tarp under the stars every night for slumber parties. The growing competence of the younger set as paddlers, to the point that some became world class kayakers, and all of them grew almost flippant about their abilities in the familiar, yet still daunting, water. The abandoned yellow raft we came upon one year, stuck fast at the top of Snow Hole Rapid, a Class IV maelstrom of water. The time we camped at the confluence with the Snake, and the dam release upriver washed a bunch of our gear downstream. The summer of wild fires when we went around camp with bandanas pulled over our faces and the air was snowing gray flakes of ash. The lunch stop that was so hot one of the inflatable ‘duckies’ exploded.

And then there’s the tradition of full contact keep-away that we played on certain shallows along the river. In knee-deep water, using beanie baby toys as balls, it was always kids against adults in lengthy, free-for-all bouts that sometimes resulted in injuries, but were always no-holds-barred fun. For years, of course, the parents had the better of it. We could outrun, out maneuver, out wrestle all of them. We also understood that our time would come, which it inevitably did. The kids grew up and became athletes while we kept getting older and slower. Soon enough they could out run, out maneuver and out wrestle us. After a few years of that, which we understood was our due, the enthusiasm strangely withered.

One year I included my parents, then in their early 80s, along. It was the summer I had surgery to address a cancerous tumor in my left eye. The day we launched the raft that my parents would be passengers in, and that I’d be responsible for rowing safely down the river, I lost sight in that eye. I managed. It was an adventure in depth perception, as in, ‘Wow, I had no idea that hole was that big!’. I’d done the river enough that I pulled it off. For them, it was a trip for the ages, and it included one of the final spirited keep-away matches, which they watched with incredulous awe from under the shade of an umbrella stand. Two weeks after they returned home, my dad fell over on a walk, had to get a life flight to the hospital in Casper, Wyoming and ended up with a pace maker. Who says timing isn’t everything?

When it comes to family-friendly river adventures, the lower Salmon has it all. And it is reliably accessible because you don’t need a permit, yet. Show up, pay for a vehicle shuttle, and go. Most of the rest of the watercourse, equally magnificent and adventurous, requires a permit that you apply for in a very competitive lottery process. Every year, while we kept doing the lower river, probably fifteen of us would apply for permits on the Main Salmon and the Middle Fork. We almost never succeeded. Year after year we were skunked. Every so often, though, maybe once every six years, one of us would get lucky and pull a permit for another section. When that happened, everyone glommed on. Winning that lottery was rare enough that people would go to herculean lengths to make it happen – reschedule vacations, miss weddings, finagle work. You get an invitation from the lucky winner, you go.

Even now, when the kids are grown and running their own trips on the lower Salmon, when somebody in the clan pulls a permit and you get invited, you tend to fall prey to that same urgency to join. When Martin and Billie pulled a Main permit in July, and invited us along, we didn’t really hesitate. We didn’t ask who was going or how long we’d be or how the logistics would go. We just said yes, and then inquired about the dates.

As these trips go, the group is pretty manageable – just 10 of us. Two rafts and four inflatable canoes. It isn’t the first rodeo for anyone, and most of us have been on numerous trips together, including this stretch of river. But every group comes together with its unique chemistry and challenges. Scott and Randy are soloing their inflatable canoes for the first time ever on big water. They are a little nervous, talk a fair amount about strategy and agree that if things don’t go well, they can always roll up one of the boats and team up. Martin, as the permit holder, is feeling responsible and a little uptight about all the camping and river decisions. He roams around the campsites at the Corn Creek launch talking to people about cooler size, room for gear in the two rafts, camps we should lobby for, strategy for departure time. Everyone, including us, is a little preoccupied and distracted by the whole business.

There are aspects of these bureaucratically managed, popular rivers that I find crazy making. I get the need to manage the onslaught, to assign camps, to make sure everyone is prepared and aware and blah, blah, blah. Still.

In the morning, we join the shit show at the ramp, along with several other launching parties with their dogs and rigs and pirate flags flying, everyone jockeying for spots, competing for the best camps, jovial and friendly, but with that competitive edge. Then we troop up to the ranger station and get the briefing, do the paperwork, check the boxes, settle up our fees. How to have fires, how to brush teeth, how to poop, what to do with garbage, whether to worry about snakes or bears, how to treat petroglyphs and artifacts, and all the rest of the minutia and protocol. Kind of drives me nuts. Part of me wants to boycott all the regulated rivers like the Salmon and the Colorado in the Grand Canyon, despite their beauty and compelling adventure, and instead, make do with maybe less stunning water without all the hoopla and regulation. Sometimes the hype is so over the top that it takes the shine off.

It is nearly mid-day by the time we push off and feel the first tug of current under the hulls. The tension dissipates a notch, just to see the ramp disappear around the bend, to anticipate the first rapids, to lose sight of cars and other raft parties and break through to that other dimension dominated by current and canyon, bird and bighorn, weather and rapid, shade and sun. The first day is just 10 miles, and it goes by quickly, with only a few minor rapids, spots of cloud and sun, maybe some building potential for rain.

So. When Marypat asked me what I was going to do about my drinking, I honestly didn’t know, except to acknowledge the need to do something. As it happened, I stopped that day, on our way back from the family reunion. I couldn’t come up with a good reason not to. Honestly, when would be a better time? As I had previously, when I made the decision to quit, I went cold turkey. No weaning myself a bit at a time, no going to AA meetings, no sneaking around or rationalizations. Just stop. And I didn’t talk about it. Not a matter of dignity or anything. I just didn’t want to discuss it or get into any backstory. And, if it didn’t stick, I didn’t want to raise expectations by making it a big deal.

My strategy, when offered a beer, was to say, “I’m taking a break from alcohol.” Leave it at that. People understand. I mean, who doesn’t need to take a break from alcohol from time to time? It doesn’t mean I’ll never drink again, although that may well be the outcome. It isn’t some noble campaign. It doesn’t cast aspersions on them for their drinking habits. Just taking a break. People get it.

It’s what I say to Scott the first night on the Main Salmon when he offers me a cold beer out of the cooler. I’ve known Scott for a long time. Long enough that he’s well aware of my issues with drinking. The truth is that everyone knows, despite the fact that I carried on as if nothing was wrong and I had everything well in hand, everyone who knew me well also knew that alcohol was a struggle for me. So Scott just nods and closes the cooler while I go grab one of my cold, sweaty, ersatz beers from mine. No biggie, yet it feels like a hurdle to get over.

The Salmon is a magnificent watershed. It starts in the Idaho high country near Galena Pass, gathers itself into a significant river by the time it passes Stanley, Idaho, where people start to put boats on it. From there all the way down to the Snake, the river lopes through dark canyons, drops through frothing whitewater, offers blue-ribbon fishing, carves its way down past Challis and Salmon and turns west into the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness, one of the most impenetrable wild blocks of country in North America and the main reason the driving shuttle is so god-awful long! Small price to pay.

The Yellowstone River in Montana is lauded as the longest free-flowing, undammed river in the Lower 48, despite the fact that it includes a half dozen diversion structures along the way that could be mistaken for dams, even if they don’t fully stop the flow. The Salmon is nearly as long and doesn’t have that asterisk on its undammed qualifications. Along the way, several of the major forks, like the Middle Fork and the South Fork, are substantial, magnificent rivers to run in their own right. The Middle Fork may be the single most prized whitewater trip in the west, and the permit competition to get on it is fierce.

Top to bottom, the Salmon is full of heart-stopping rapids, hot springs, lovely beaches, sweet groves of shade trees, and mile after mile of green, fast, heady current that gives boaters a ride for their money.

One of the topics of conversation in our first camp centers on the possibility of doing an end-to-end Salmon trip, either from Stanley all the way down, or from the put-in on the Middle Fork down to the Snake. It would take almost a month to pull off, and some fancy scheduling to line up permits, but it would be a helluva trip. The main permit season ends in early September, and our thought is to go right after that and spend September on the Salmon. Has a certain ring to it. People could do the whole thing or join up for a chunk. Now that many of us are either in or approaching retirement, why not?

Conversation is interrupted by a rain squall and the scramble to set up a tarp. Dinner is interrupted by a short but intense hail storm. After dinner it gets chilly and everyone heads for the tents and books. Officially on the trip.

From his tent, Randy announces the time of sunrise, to the minute. He has an app for that. And he has the excuse of being a professional cameraman for whom sunlight matters a great deal. Still, it takes all the fun out of guessing.

“Criminy,” I call back, “what isn’t there an app for?”

The overhanging preoccupation on the Salmon, whatever section you do, is whitewater. It isn’t all white knuckle, world-class stuff, but it is pushy enough to merit attention and just when that attention wanders, or you don’t take a drop seriously, bad things will happen. We’ve all experienced that lapse, and the spank of consequence. No one wants to swim.

On Day 2 the big event is Black Creek Rapid, a ‘new’ bit of whitewater that cropped up after a side creek flooded and reconfigured the river in 2011. Black Creek is preceded by Salmon Falls, which used to be a notable drop worth scouting. I remember that rapid, and the importance of hitting the ‘tongue’ of smooth water just right. If you did, it was a fun, rollicking ride. If not, well, then it was survival. Salmon Falls, however, has disappeared. A testament to the dynamic life of a river, the same flood that created Black Creek completely blew out Salmon Falls. This day it is barely a ripple in the current. A bit downstream, however, all that flood-borne debris, and the stuff that used to make up Salmon Falls, came to rest in a massive jam that first dammed up the river entirely, and eventually created the brand new whitewater challenge. As we approach, the river horizon drops away.

Even the scout is daunting. Lifejackets are called for, because the scramble to have a look crosses steep, slick rock faces and if you slide into the river on the way, you will be swimming the rapid. Three rafts have pulled in ahead of us. As we approach the best vantage to scout from, the raft crew is coming back to their boats.

“We’re running left,” the leader announces, “but with those little boats of yours, you might want to go right.”

The only other time I’ve run this drop I ran left. It was years ago, at a different water level. I remember it as being a solid drop, but very doable. Looking at it today, the run is chaotic with choppy, conflicted waves and big hydraulics.

“Left, you say?” questions Scott, looking it over. “Doesn’t look so great to me.”

“Yeah,” I say. “This is much different than I remember.”

On the far right a big tongue of river leads into a whopping wave train. Looks like a wild ride, but a straightforward one. Scott and Randy are particularly nervous. This is their first real test in solo mode.

As we contemplate and discuss, the first raft with the leader at the oars pulls into the river. We watch. He heads for the left side, pulls away from a rock, drops over the edge. The next second he is tossed like a rag doll out of the raft. His passenger stays aboard and scrambles to grab the oars while the captain washes downstream. The next raft is right behind and the same thing happens. Over the brink, the oarsman tossed unceremoniously into the drink. Then the third. This time the man on the oars is well aware it’s going to be a rough ride and braces for the assault. He gets thrashed around, his body whiplashing back and forth, but just manages to stay on board.

“I’m thinking we should go right,” we all chorus, and start back to the boats.

One after another we pull away, into the current, line our boats up above the broad, fast tongue of water and the waves below. One after another we gather speed, keep our boats straight, paddle hard over the crests, get thoroughly doused wave after wave. Only remember to whoop once we’re through, because the rest of the time we were holding our breath.

On we go, past the bedraggled trio of rafts who have collected themselves in a small eddy across the flow, but are a pretty quiet bunch. That’s the humbling power of this river. Just when you get cocky, it slaps you down.

Day 3 is an even bigger whitewater stretch. Marypat and I have a tradition of switching bow and stern positions each day. It’s a habit we established years ago, and it changes things up, gives you perspective, helps you appreciate the challenges and viewpoint of each position in the boat. It’s Marypat’s day in the stern and there is a steady parade of big rapids like Bailey’s and Split Rock and Big Mallard coming up.

Teamwork in a boat is a tricky, elusive matter, and it keeps evolving. It’s not like you achieve a level of competence and then stay there. Like all the other aspects of a relationship, things keep shifting.

The summer we first met we went on a month-long expedition in northern Manitoba, down the Seal River and along Hudson Bay. Marypat had essentially never paddled before. I was the experienced one, the teacher. Luckily Marypat was a quick learner. A couple of days in the stern, with me monotonously calling out the correction stroke she needed to keep the boat straight, and a few days in the bow with me pointing her at obstacles and forcing her to react was enough. She had all the other backcountry qualities in spades and took to paddling the way she took to most sports all her life. If anything, early on, she was naively cocky about whitewater. These days she’s more nervous than cocky when we come to a rapid.

Over the decades since that first northern summer we have paddled boats together over thousands of miles, across continents, down lakes and rivers, past portages and falls, from the Far North to Mexico. We often go hours without a word, paddling in synch, reacting to each other’s body language, making the boat go as unconsciously as walking a trail. For most of that time, we’ve prided ourselves on not capsizing. We didn’t go over in a canoe for decades. Of course, that distinction inevitably came to an end, but we have been a team in a boat as much as we have been partners in life. Being in a boat together is as good a test of a relationship’s worth as anything. Maybe we could halve the divorce rate in this country if we had couples hitch up in a canoe for a week before they took the leap.

Even so, there have been rough patches for us, days when we aren’t in synch, when words are indeed spoken, and at some volume. Rapids that, if they had been a dance, we would have been stepping all over each other. One person decides on a route while the other horses the canoe towards their preference, with consequences, for example. Failures of communication. There are days on the water when that line between love and loathing becomes thin indeed.

Marypat, for example, tends to think I let up paddling too soon at the end of a rapid. Sometimes she’s right, and we get surprised by an upwelling or boil, but it seems to me that she’s made the point enough and that it isn’t strictly necessary to say “Keep paddling!” every single time we finish a bit of whitewater. On my part, I tend to think Marypat doesn’t value or employ a stout brace in the stern when we rollick our way through a wave train. Like that.

So there is always that tension about what sort of day it’s going to be on the river when rapids are coming up. Will it be a triumphant display of flawless teamwork or a humiliating descent into mediocrity and bad choices? Usually it’s a mixed bag, some stellar runs and a few flawed moments to keep egos in check.

The Salmon is a classic, pool-and-drop river. Big rapids separated by calm stretches of current. In other words, time to regroup and recover and relish between bouts of excitement. After a brief rain shower at dawn that gets everyone up and scurrying to gather gear, we are on the river early and stop to scout the first rapid just downstream.

“Let’s keep talking,” Marypat stresses like a coach in the locker room at halftime. “Let me know what you’re doing and I’ll do the same.”

We stand by the river, talk through the run, listen to everyone else strategize, pick out our markers to read off of. Then we clamber back to the boats over boulders, kneel, tighten up thigh straps, settle in. One last meaningful look between us and we peel out into the current and let it play out, sometimes just as planned, sometimes making it up as we go.

That’s how this day goes. The buildup of a rapid. The discussion. The heat of watery action. The calm after. And the debrief.

At Big Mallard, Scott and Randy, by now feeling pretty comfortable in solo mode, decide to try a new run on river right. It looks doable if they make the right moves. Scott goes down first, gets momentarily caught in a watery hole that almost takes him over, but manages to pull out of it. Randy goes in to the same hole more sideways than he should and his boat goes over in a flash. The rest of us stay on river left and navigate a narrow chute between a rock and a massive pour over. It feels skinny as hell, but we pop through unscathed and head down to help Randy collect himself.

For Marypat and me the day goes well. We make our runs pretty much the way we plan. We talk to each other. I keep paddling at the end. Marypat braces in the waves. We stay upright and bump lifevest chests in triumph when we get to camp.

The days start to meld, as they should. Rapids and weather and camps and a gathering comfort with each other’s company. We decide that the trip bird is the Lewis’ woodpecker, which undulates across the river multiple times a day, or scrabbles up the sides of dead snags, stopping to hammer away for insects. That or the canyon wren that serenades at dawn and dusk.

It gets hot.

“The sun is always welcome when it arrives in the morning, and nice to see go every evening,” I remark.

Some nights we sleep out under the stars. Marypat and I are trying out a double sleeping bag with the name, Dream Island. Scott asks us each morning how our night on Dream Island went. Dreamy, I say. Most afternoons we arrive in camp well before the sun goes down – and we know the precise moment it will drop over the horizon, thanks to Randy’s app. For hours we dip in the river, hang out in the shade, sip cold drinks, read and chat. It is a veteran crew. Camp chores get done without fuss. Dinner prep and clean up is rotated around. By the third or fourth day, the rhythm settles in. I love that sense of having forgotten about the trip launch and not yet considering the take-out. Unfortunately, I know we’re more than halfway, and that we’ll be collecting into cars again before I’m ready. I warm to the idea of that September on the Salmon fantasy trip. You could get used to this, week after week.

Even on this wild section of the Salmon, there are a few isolated human residents, and the history those who came earlier. We pull in at Yellow Bar Ranch, below Big Mallard Rapid, and walk up a long sloping trail to the house. It is set in a lush green lawn, irrigated with river water, with islands of trees and garden plots. Greg and Sue Metz care-take the place and give us a tour. They have lived along the Salmon, care-taking several places, for more than 30 years. They hadn’t been out since October, some 9 months, but it’s not as if they don’t see people.

“There are busy days when we probably give the tour to 100 people,” Sue says, more cheerfully than you’d expect. She takes us around as if we’re the first, open to questions, sharing their space, pointing out ripening vegetables and the wood-fired hot tub.

“There are eight full-time residents along the river corridor,” Sue tells us. “We get our mail by airplane, or sometimes by jetboat. And our biggest fear is fire.”

Greg keeps himself busy with a hobby/business of knife-making, using a foot-operated metal hammer and primitive forge. He takes us through his shop and shows off his wares. Their lives are simple, even backwards by mainstream standards, but it’s hard to find them lacking in life’s riches. No they don’t have a Costco nearby, or a movie theater, or traffic, noise, pollution, job hassles, advertising distraction and the rest of it.

Do they sometimes feel isolated, a little lonely? Probably. Are they a little exposed when it comes to rescue from calamity? Yeah. Would they trade? Emphatically not. Walking around their place, glimpsing their routine, appreciating the landscape, imagining the space and quiet and mental clarity that would come from their lifestyle, putting myself in their shoes, I wouldn’t either.

Not everyone is cut out for the isolation and self-reliance a life in the depths of the Salmon River wilderness imposes. But a few notable people have thrived on that existence.

The next morning we drift in to Five-Mile Bar to check out the spot occupied for half a century by ‘Buckskin Bill’. The homestead is now a combination museum, store and tourist stop. Born Sylvan Ambrose Hart in 1906 in Indian Territory, now Oklahoma, Buckskin Bill earned a reputation as one of the last true mountain men. College educated, with a work background in the oil fields of Oklahoma, Hart left that life behind when he bought 50 acres of land at Five-Mile Bar for $1. He lived there for more than half a century, until he died in 1980.

Buckskin Bill was a colorful character who dressed in homemade clothes, sported an untamed bush of a beard, constructed stone buildings by hand, and made many of his own tools, armor and weapons. He hunted and fished and grew vegetables to sustain himself, sprinkled in stints of trail-maintenance work for the Forest Service along this stretch of the Salmon, and ended up with a fortified homestead featuring a 2-story house, a blacksmith forge, a turret reminiscent of the Crusades, and an underground bomb shelter.

Hart can be forgiven a measure of paranoia. He watched while wilderness designation of the Frank Church Wilderness and Wild and Scenic status granted to the Salmon River threatened his right to live on the land. He was ready to go to battle defending that right. After his death, Hart was memorialized in nearby Grangeville, Idaho and is buried on his unique piece of wild country.

Bumping downstream after a warm night sleeping out on a sand beach, we pull in at the inaccessible Bemis homestead, a site on the National Historic Register. Polly Bemis is the star character. Born in China in the mid-19th Century, enduring the tradition of bound feet, and sold off by her father for a few bags of seed at the age of 18 during a drought, Bemis’ story is shrouded in mystery, but even the bare bones of her life are incredible.

As a young woman, the diminutive Bemis was smuggled into the US where she was sold as a slave for $2,500 to a wealthy Chinese man. She landed in Idaho where she worked at the saloon run by her owner. How she gained her freedom is the subject of speculation, but whether she was won in a card game or granted freedom by her owner, she eventually teamed up with Charlie Bemis who protected her from further peril. Polly and Charlie later married and they staked a mining claim up the Salmon River where they lived together.

Polly was known for her sense of humor, her love of children, and her skill as an angler. She spent years fighting for her American citizenship, finally granted in 1896. At the homestead they survived a fire in 1922 that burned their home to the ground. Polly is credited with pulling Charlie’s body out of the fire and saving his life. With the help of neighboring ranchers, Bemis slowly rebuilt on the same site. Charlie died later in 1922, but Polly lived on the homestead for another decade before she died in 1933.

Today the grounds are spacious and well-cared for, with sprinklers irrigating green lawns, flourishing gardens and shaded buildings. Polly is buried here along the peaceful river where she lived out her otherwise fraught, hardscrabble existence.

Before dawn on our final day, we cluster around the camp table and warm our hands with mugs of coffee. It isn’t rushed, but we have the boats packed and shove off by 8 am. It is a schizophrenic day, half on the river navigating several notable rapids, and half on the road, driving the long slog back home. Given the whitewater challenges highlighting the morning, it isn’t worth getting ahead of ourselves. One rapid at a time.

I tick them off. The first, Dried Meat, is a Class III drop with a clear tongue of water at this level. We run it clean without stopping to scout. Chittham Rapid is more complex. We bunch in along shore well above and stumble down the rocky bank to have a better look. After the obligatory discussion, we hang right through the conflicted waves and bigger holes into the eddy below. Scott gets a surprise slap by a side wave at the end of his run, doesn’t brace in time, and goes over. He comes up with that universal expression of shock and chagrin.

“Where did that come from?” He dog-paddles in and regroups. No one laughs, at least not right away.

Finally, Vinegar, another Class III with daunting potential for pushy waves. I remember a run here in the boat with Sawyer where we got shoved sideways by a diagonal wave and Sawyer saved us from capsizing with a well timed draw. We stop, have a look, discuss and point and huddle up with partners. All of us sneak the right bank, staying clear of the impressive waves mid-river. No problem.

The final miles are a lazy float to the boat ramp with a few drops to keep us cool and alert. Then the mad scene on the concrete skirt angling up from the river with other parties coming and going, rigs backing down to the water, people finding keys, washing boats, wrapping things up, reorganizing, donning travel clothes, reclaiming wallets from the bottoms of clothes duffels. The mandatory final group photos, the promises of future trips, the gritty hugs.

Before we break for vehicles and air conditioning and the marathon drive home, I say, “Don’t forget, next September on the Salmon!”