CHAPTER 4: AUGUST – FINALLY

This one was a long time coming.

For decades the Far North was our calling card. Our relationship adventures began in 1982 on the Seal River and Hudson Bay in Manitoba. The first summer together as a couple, and a northern river wound through it. From there, almost every year, we paddled rivers in the Yukon, Alaska, the Northwest Territories, Nunavut, Ontario, Labrador and northern Quebec. Year after year we were enticed back north by the vastness, the water, the tundra, the peaks, the solitude and breadth of terrain that harkens back to a time when expeditions weren’t such managed, high-tech, hyped-up affairs. Back to a time when you could get a train engineer to stop alongside a lake, unload your outfit, and wave you off for weeks or months before you’d pop back up at another train trestle, flag down the next freight, and find your way out.

Our love for that northern country came to a head during two trans-Canadian journeys, five years apart, that included winters spent on the shore of Lake Athabasca, just south of the border with Nunavut. Those years amputated from the mainstream, embedded in silence, hardly ever separated from each other by more than a dozen feet were profound the way war or poverty or the Peace Corps are profound. They changed us, centered us, realigned our perspective permanently, even if that perspective gets blurry sometimes in the cultural onslaught.

It has been a sweet honor to share that land with our kids, taking them on extended trips through the Barrenlands, or down the Yukon River, or summers in Saskatchewan and Manitoba, where they transformed from dependent children to full partners who know how to make fires, cook food, set up shelter, portage loads, and who fell in love with the power of that unique place.

But it had been years since we’d gone north. Summers went by full of other distractions, other journeys or responsibilities. We’d talk about it, look at maps spread on the living room floor, scan the trips still on the checklist to get to one of these days. And the days kept passing. Northern expeditions are demanding in every way – physically, financially, logistically, mentally. It helps to be young. No telling how long that window of possibility would stay open. An urgency grew in both of us.

We almost pulled it off the summer before. We talked Sawyer and Ruby and their friends into joining us on another expedition. We had a route picked out, some travel logistics in place, dates bracketed on the calendar. All of us were drying food, thinking through the gear, putting money aside. It would have been another month-long immersion concentrating on the tundra country that carries such weight with us, that land north of trees, but full of wolves and musk ox and caribou and Inuit artifacts.

Sometime that February Marypat and I were sitting in the living room in the pre-dawn dark the way we do on winter mornings. We hold coffee mugs, silently greet the day, don’t talk, let the peaceful gray hour settle around us before the day takes off.

“Something’s wrong with me,” Marypat said from the darkness across the room. “I don’t know what’s going on, but I’m not right.”

She had been complaining off and on about full-body achiness. It was taking her longer to recover from ski outings than usual. She would go out on a tour that normally wouldn’t phase her, but have to recover for a day before doing something again. She is a bit on the driven side when it comes to exercise, so I didn’t make that much of it at first. We are getting older. No wonder we can’t pull off the stuff we did when we were 30 and bounce right back the next day.

We’ve reached an age where aches and pains are the normal state of affairs, when a long drive in a car requires a few minutes before we can stand up straight, and where unexpected symptoms strike out of the blue. I had noticed that Marypat wasn’t her usual self, but her usual self is pretty off the charts, so I was tempted to chalk it up to higher expectations than were reasonable and the unfortunate fact of aging. I didn’t say that. I listened as she described the all-over stiffness, the instability, the pain and fatigue. I wanted to deny, to sympathize but also assume it would pass. But there was something unavoidably real and fearful in Marypat’s voice.

It didn’t pass. Instead it progressed. Over the weeks she moved more and more like an elderly woman. When she got out of bed she had to stand to get her strength and balance before she took a step. She was in such pain that it was excruciating for her to roll over in bed.

The road to a diagnosis and a treatment regime was exasperating. Over the months Marypat changed up diet, saw her doctor, got tests, took it easy because she had no choice. Her inflammation numbers were off the charts. Some days she could barely move. Just standing up was torture. It seemed that she was probably suffering from one of the many autoimmune syndromes that seem to be proliferating, but what? She called every rheumatologist in Montana and couldn’t get an appointment for months. She even tried Idaho offices with no better results. One local doc came highly recommended. Marypat got on her waiting list and called every morning to see if there was an opening. She got to know the receptionist really well.

We were talking to a friend who works at the hospital about her situation and she was stunned that we couldn’t get an appointment. “I’ll see what I can do.”

A week later we got in. Don’t know if it was Marypat’s daily calls or our friend’s advocacy, but we finally could get some help.

We both went to the appointment so we could each hear and interpret the findings. The doc listened to Marypat’s description of her symptoms, looked over her blood work, ordered some more tests, but by the end of the session, was pretty confident that what she had was Polymyalgia Rheumatica, an autoimmune disorder shrouded in mystery, but, according to her, with a pretty solid treatment regimen. She wanted to do more tests to confirm her guess, but she outlined the plan, which, simply put, was a years-long course of cortisone drugs, on a tapering schedule. Her hope, which Marypat settled on as a certainty, was that one year of taking the drug would do the trick.

“We don’t know exactly what triggers this,” she said, “but if you follow protocol and stick with the plan, I expect you to be cured for good at the end.”

By this point it was spring. Our trip was a few months away. I couldn’t imagine how Marypat could expect to paddle all day every day, shoulder portage loads, and participate in all the camp chores on a month-long expedition, but she wasn’t ready to pull the plug.

“Let’s see how it goes,” she said.

Cortisone is one of those miracle drugs. It makes you feel like you can do anything. Still, for Marypat, it took a while. We went out for a short stint on the East Gallatin in early May, just a couple of hours of the usual paddling gnarliness. Marypat couldn’t open her hands for the next three days. At the end of May, when we took on our annual Three Rivers challenge, Marypat participated, but on the last morning, she announced that she didn’t think she could do the summer expedition. That admission was huge for her, to give in to a physical limitation. For the rest of us, it was a pretty obvious conclusion, but for her, it was an admission of failure.

“I still want to do it,” she said, eyes blazing. “I just don’t think I can handle it this summer.”

Over the summer and on into the following school year, Marypat came back. She came back remarkably. She got on her mountain bike, rode in races, hiked and paddled and skied. Cortisone combined with her indomitable will healed her in amazing fashion. It was a long haul, but something to watch, as her dose kept tapering and her strength kept returning. At some point we had to start planning for the summer.

The kids requested a trip of three weeks, more or less. They all had jobs, school, financial issues. Anything longer would be tough. The problem was that three weeks wouldn’t cut it for the trip we had planned the year before. The perennial challenge, putting together a trip to match our desires, our budgets, our abilities. The Far North is seamed with rivers that spider-web across the vast wilds, pocked with lakes, some of them huge. In some quadrants there seems to be more water than land, but conjuring the route that is remote and spectacular, yet accessible and doable, can be torture.

I put out some feelers to friends in that small circle of humanity who have fallen prey to the same obsession for paddling through that boreal and arctic landscape as we have, people with dozens of canoe expeditions on their life lists. Some interesting candidates came back.

It didn’t take that long to narrow the list to half a dozen, and then to two or three. I found route descriptions and trip accounts and we had a group meeting to hone in on preferences. It came down to two rivers – the Noatak in Alaska or the Mountain in the Northwest Territories. Both flow through vast, stellar country, both offer ample opportunities for hiking, both are mountainous and full of wildlife. In the end it came down to dates. To do the Noatak justice would require the better part of a month, and several days of travel there and back. The Mountain could fit into that three-week frame and allow for plenty of time to dawdle along, stopping for hikes and enjoying the immersion.

Once the decision was made, the vortex of logistical decisions exerted its gravitational pull. We researched different travel modes, different access points, renting from outfitters or bringing our own boats, finding bush pilots, ordering maps, crunching the numbers, dehydrating food. Phone calls, internet research, conversations with outfitters and pilots, budgeting money and time, nailing down dates. Over a period of weeks it came into focus, we found helpful contacts, settled on an outfitter and a flight service, pored over the map quads and scattered trip reports, figured out a travel plan. Dehydrators hummed away in every household. Gear was assessed, repaired, borrowed, ordered.

For a while the trip loomed on the distant horizon, months and months away. Preparations felt leisurely, comfortable. But suddenly, before we felt truly ready, our departure date was a week away. It always happens that way, no matter how far in advance you start. It’s simply the way these journeys unfurl. People and gear collect, details get tucked into bed, the little emergencies that can’t wait get dealt with, the last minute list is finally checked off before piling everything into two cars, all of us climbing aboard, and caravanning north toward Edmonton, a long day’s drive away.

What should have been a seamless travel plan was anything but. As long as we had our hands on the wheel, in control, we were fine. Into Edmonton, long-term parking arranged, a marginal dinner out, a shuttle to the airport at 5 am . . . From there everything unraveled. At the airport we loaded on the plane and sat there an inordinate amount of time, until finally the pilot announced that he had good news and bad news. The bad news – something was wrong with the ventilation system and we couldn’t fly. The good news – another plane was available so we’d be delayed, but we’d get out.

Several hours later we hummed north over the rivers and forests and lakes of Alberta, some of it familiar, and on into the Northwest Territories, across Great Slave Lake, landing in Yellowknife. After reshuffling at the airport there, we were on our way to Norman Wells, along the Mackenzie River, where our outfitter and bush pilot waited. Fifteen minutes from landing a man sitting in front of me started complaining of discomfort. Turned out he was a diabetic with heart issues. A nurse was called to attend. He didn’t seem particularly distressed, but the plane turned around, heading back to Yellowknife and medical services. Frustrating, but understandable. Drone all the way back to Yellowknife, deplane, mill around in the airport waiting for a plan to emerge.

Waiting, waiting, until finally a barely audible announcement was made that the plane couldn’t fly because the seal of the first aid kit had been broken. Rules, you know. Everyone was encouraged to get in line and negotiate their arrangements with the two harried ticket agents available. As the line of maybe 100 people inched painfully forward rumors flew, Plan B’s flew, questions arose, like, “Are you telling me they can’t find another first aid kit and put it on the damn plane?” There was talk of booking a charter flight at significant extra cost for those who really had to make their destination. When we finally got to the front of the line, Sawyer and I told our tale to the ticket agent, whose only option for us was to fly back to Edmonton, where we’d have to wait three days for the next flight north with room, by which time our bush pilot would not be available and our trip might well be impossible.

“That’s our option?” Sawyer asked, incredulously. The agent nodded. “No other plane available? No refund of our tickets? Go back to Edmonton and wait three days?”

“Best I can do,” she said. “I’m happy to give you the number for our Customer Service Department.”

Meantime, the rest of the crew had been talking to the charter faction who were drumming up people to fill a plane like hucksters at the county fair – the more bodies they could get, the cheaper it would be. We called the outfitter to see how much flexibility we had. Not much, it turned out. The bush plane was booked for days. If we couldn’t make it, we might have to cancel our expedition.

In the end I handed over my credit card, cringing, and we climbed aboard a jam-packed prop plane that flew into the lingering twilit northern sky, heading for Norman Wells again. And it was well after midnight by the time we got to the outfitter base where we had a cabin lined up and our rental boats waiting. And it was just after breakfast, the next morning, still numb from the travel epic, when our bush pilot showed up, bright and energetic, wondering if we’d have the first load ready to go in an hour. Sure, we said, we can probably manage that. At least someone was finally being efficient.

Oh, and somewhere in the two-day travel trauma, I’d lost both my Medicare and Social Security cards. No idea how or where, but they were gone.

There are portals we go through, passages between dimensions, worm holes, time warps, whatever you want to call them. The flight from the float base near Norman Wells to Dusty Lake, the tiny speck of water near the headwaters of the Mountain River, was one such portal. Through it we flew – away from something, closing behind us as palpably as a swinging door, and into something altogether different.

Sawyer and Quinn went with the first load, which included the bulk of our trip gear. The small, powerful Porter idled down the lake, turned, and roared back into the breeze, then banked away in the distance. Sudden as that, they were gone. How quickly we would follow was unknown. The bush pilot had other trips to juggle. The two of them would start portaging loads the half mile or so from the lake to the small ribbon of river near the divide between the Yukon Territory and the Northwest Territories, about a degree shy of the Arctic Circle, high in the Mackenzie Mountains, a serrated range running like a ragged zipper between the two Canadian territories and the watersheds that flow away, east and west. If we didn’t get there later in the day, given variables from weather to shuttle schedules, they had what they needed to spend the night and wait for us.

The four of us left at the base checked through gear, winnowed out the things to leave behind – money, passports, travel clothes – then waited for the drone of approaching plane. By lunchtime the pilot was back, jaunty as ever, stepping down onto the float from the cockpit, pulling out his phone.

“We’d really like to get up there today,” I said.

“I thought you’d want to give them plenty of time to carry all the gear,” he joked.

“Tempting,” I said, “but if you’re able to do another run, that would be great.”

He called his dispatch, had a short conversation, put his phone back away.

“Alright then,” he started pulling the hose from the 55-gallon drum to refuel. “Let’s go. I’ll get lunch when I get back.”

In we piled, with the remaining gear and two canoes strapped firmly onto the floats, one on each side. Slowly back down the lake, turning, roaring back up, breaking free, banking sharply around. Into the blue void of sky. Away from all the clutter of life, like cutting the umbilicus.

Ruby’s boyfriend, Everett, grinning like a ten-year old with a new bike, got the co-pilot seat. From the air the country we’d gazed at on topo sheets spread out below. The massive ribbon of the Mackenzie, a river almost oceanic in scope, measured in the millions of cubic feet per second, miles wide in spots. And across it, over the flats of the valley, and quickly, into the foothills and rising mountains. A pair of moose high-stepped out of a marshy lake at the noise of the plane.

The pilot said something about seeing a herd of caribou on the first trip and did we want to zoom down to look at them. Might make the flight a little bumpy, he added. Ruby and Marypat are notorious for motion sickness, but Ruby gave the thumbs up and Marypat nodded gamely. The plane banked hard over a broad plateau of high country. Sure enough, the caribou were there, a scattered herd grazing in the tundra stubble on the mountain slopes. Caribou and some Dall sheep to boot. Everett took pictures, pointed to things. About then, as predicted, the flight got bumpy. Marypat and Ruby, as predicted, reached for the puke bags, started simultaneously retching, hunched over in their seats. The pilot did his best to avoid clouds and turbulence, but that glimpse of wildlife was the end of the fun for them.

I did my best to be sympathetic, while also trying my best not to focus on the gagging. And I couldn’t stop gawking. Clefts of river valleys roping through the range, cliff-guarded canyons, high plateaus, craggy peaks and long rock ridges, occasional glaciers. In every direction more of it. More mountains, more valleys, more stupendous peaks. The plane thrummed just above the highest peaks and ridges. It went on out of sight in every direction. More of the same. We would be dropped in to one wrinkle in a land full of similar wrinkles.

One valley in an expanse full of dramatic landforms.

This quadrant of wild country is one of the most extensive, intact ecosystems on earth. It is veined with massive rivers. We would paddle down one ribbon in a section of the Far North full of similar watery ribbons – the Wind, the Bonnetplume, the Snake, the Arctic Red, the Nahanni, the Keele – every one magnificent, extensive, draining watersheds the size of states. Any one of those rivers would be a major paddling mecca if it were located in the lower 48, probably only accessible by lottery to keep numbers down. It will seem vast and all-encompassing, once we are swallowed up in it, but the Mountain is only one valley in a vast horizon full of other valleys equally all-encompassing, equally full of mystery and grizzly bear and quiet drama. The plane was a tiny dot in the vast sky, and we would be tiny dots of color in a tapestry of mountainous land sprawled around us, horizon after horizon of it.

And then we were in it. Through the portal. Dusty Lake, tiny looking, shallow and dingy and too small, lined up below. The Porter angled steeply toward the watery dot. I took another 360-degree look, then the plane hit the water and pulled up hard, just shy of the far bank. Sawyer and Quinn sat, small colored figures, next to a canoe on the shore. We taxied slowly toward them. In minutes we unloaded, apologized for the puke bags, waved goodbye, and the plane roared off again, waggled wings at us, and was swallowed in the sky. Silence swooped in around us, a universe of it.

#

At the end of the only known portage of the trip, less than half a mile from Dusty Lake, the Mountain River churns past, muddy and small, shallow, with humps of rocks breaking up the flow. Here, only a few miles from the divide that separates the Mackenzie drainage and that of the Peel River, both behemoth watersheds, the flow is about like the East Gallatin back home, a channel a single tree could block.

The only portage of the journey, from Dusty Lake to the headwaters.

We had heard there was a waterfall upstream and Marypat lobbies to go looking for it. She and Ruby could use the walk to settle their stomachs. I tamp down my tendency to move on, see what’s around the bend, take the measure of the new river, find a camp. This is not that kind of trip. We’ve granted ourselves 18 days to do a trip that some people do in 10 or 12. We have consciously allowed for exploration, for layover days, for hikes and relaxed time in camp.

We grab bear spray, secure the boats and scramble out of the shallow valley. Mountain tundra sweeps away to steep rock slopes, which sweep up to peaks and saw-toothed ridges. The ground is hummocky, a bed of sphagnum moss and grassy tussocks, dense thickets of willow, all of it furrowed with game trails. Caribou tracks in the soft ground, sparrows flitting through the underbrush, silence. We make our way through the labyrinth of vegetation, following and losing game trails. It is warm. No bugs cloud our heads.

We had been told that the Mackenzie Mountains were free of the dense insect populations the north is so famous for, but we didn’t believe it. We had all brought our bug shirts, headnets and plenty of repellant. We walk through the landscape we know should be humming with mosquitoes and black flies. No one jinxes the magic by saying anything.

Half an hour in, Quinn says she is going to lie down in the inviting beds of sphagnum and take a nap. She is getting married in September. The last months have been a whirlwind of work, school, and wedding preparations. Her parents were not pleased that she’d signed up for this, but she’s been determined that she wouldn’t be left out. She has been part of our family adventures since childhood – hikes, mountaineering, ski trips, rivers. She can’t imagine being left out. But she is exhausted.

We walk on. Another half hour and the river canyons up through a rocky cleft. We hear the small roar of a waterfall, then stand at the lip of the bedrock ravine with muddy water cascading over it. We look around at the high bowl of country leading to the mountain divide, with the cup of valley just beginning, bubbling up magically out of springs and melting permafrost and ice fields, the first gathering of a river we will ride all the way down to the Mackenzie.

Near the headwaters of the Mountain the channel squeezes through a rock cleft.

Luckily, Quinn hears us talking as we tromp back and she appears out of the low willow thickets. If we’d been silent, or if she’d been sound asleep, we could have easily walked right past her.

For days the place engulfs us. The sense of entering something rare and untamed and overwhelming is inescapable and exhilarating. Everett, especially, is blown away by the dimensions of it. He’s never been anywhere like it. Our kids have crossed the Barrenlands of northeastern Canada several times. Cousin Quinn joined Sawyer and Ruby on a 1,000-mile canoe journey from Great Slave Lake to Baker Lake across the subarctic of Canada. They know this kind of space, the immensity that swallows you. But these mountains, this valley, the lack of boundaries, hits us all.

So much of what we label wild, now, is hemmed in, bordered by roads, within earshot of traffic and airplanes and machinery, flanked by towns and lights and fenced farms and private property. There is always the sense of being held within a preserve, with close boundaries just out of sight. Contrived, arbitrary, held aside as tokens of what once was everywhere. You can still get lost, still get in trouble, still experience awe and danger and thrill, but nothing like this.

We wind through it on the gathering current. It feels like a living, breathing, full-throated wilderness. Here wildlife goes about its business as it is meant to, migrating, feeding, mating, hunting, hibernating, giving birth. There are no constraints. Sure the effects of global pollution, changing weather patterns, shifting jet streams have their impacts, but from the ground, none of that is manifest.

Wildlife as it should be.

Coming around one bend, a grizzly is startled from the river’s edge, whirls and runs into the brush. “Did you see that?” Everett says. “Yeah, good bear,” I answer. At another a bull caribou crosses the river, his antlers a four-foot spread, his coat a rich chocolate brown, exuding health. Moose raise their massive heads, stand quivering with vigilance as we coast toward them. Dall sheep graze on the high slopes above camp. Porcupine waddle along shore. In camp the mud is a welter of wolf, bear, caribou tracks. We stop often, wander away from the river into the maze of willows and stunted spruce, gaining elevation, looking over the long valley, finding bird’s nests, porcupine-chewed trees, bear scat. We are the transients, the guests. If anyone is out of place, it is us. We whisper down the miles, infinitesimal flecks of color and movement, current building, tributaries joining, glaciers and peaks rising away.

Making miles is not a problem. The river whisks us along. A couple of hours and we’ve taken care of the day’s distance. There is plenty of time to explore. The kids are robust mountaineers. A few thousand feet of steep elevation gain, miles of bushwhacking through willows and across wobbly tundra tussocks, not a big deal. Marypat is game as well, and not about to be left behind. From a gravel bar campsite, a ridge looms, leading to a rocky summit. They pull on day packs and go.

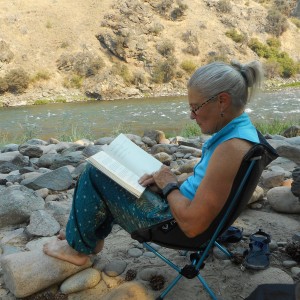

For the more challenging outings, I appoint myself to the ‘camp tender’ role. I anticipated this before the trip began. I no longer have that burning, goal-oriented urge to reach the peak, to scramble for the highest view. I know I would be the weak link the rest of the group would have to wait for. They would certainly accommodate me, but I have no interest in being the anchor holding everyone back. To be honest, I’m happy to be still, to explore around camp, to tend the fire, write in my journal, greet the day, watch what happens around me, have another cup of coffee. My experience is that, often as not, you see more sitting still than you do thrashing through the underbrush. I relish that Siddhartha-mode, the quiet of it, the mental rambling, the place taking over and stilling the monkey-mind chatter we take for normal so much of our lives.

The crew takes on a nearby peak while I tend camp.

This reckoning with age and waning ability is real. Much as I rationalize my comfort level, my new reality, it weighs on me. I have never been a driven athlete, but I have always been active, adventurous, up for challenges. To see the crew take off, bounding up slopes, navigating technical terrain, triumphant on a peak, gives me pause. I’m not doing that anymore, I think. Am I okay with that, or am I making excuses? Should I be pushing myself harder? I’m thrilled to be here, to take on an expedition, but I’m not doing what I once did. The business of aging is a tightrope act, pushing for the edge, but accepting limits and staying safe.

One morning early in the trip I am sitting by the fire enjoying another cup of hot drink, finishing a journal entry, relishing the day, while the team labors up a ridge to a nearby peak. I can see them with binoculars. The river ripples past, the flames flicker under the pot, the long-day sun rides high in the pale blue sky. They have been gone a while when I glance upstream and notice a dark stump floating in the current, coming around the bend. Then the ‘stump’ nears the bank and heaves itself out of the water, transforming into a grizzly. The bear is tawny brown with red highlights, beautiful, graceful, large, a little heart-stopping. It shakes a spray of river water into the air and ambles into the spruce forest above the river. The breeze is blowing downstream. I don’t think the bear knows I’m here, but I am suddenly less imbued with Siddhartha contentment and feeling a good deal more lonely.

I turn to face the forest, bring the canister of bear spray close, regularly check the horizon for movement, stoke the fire for deterrent effect. Time passes. I relax. The bear doesn’t reappear, but then I catch another movement upstream on the edge of vision, a flash of brown. I am suddenly on my feet, bear spray in hand. A caribou trots along the gravel bar, gives me a nervous, wide berth, clatters downriver while my heart gallops along.

Thousands of us die in traffic every year. Thousands more succumb to pollution, plane and train wrecks, deadly diets, lead-poisoning, living near nuclear waste dumps, second-hand cigarette smoke, road rage. None of that is newsworthy. It is the mundane risk of living in a ‘civilized’ world, one we all take each day without comment or much consideration. A camper gets dragged from their tent and is killed by a bear, it makes international headlines. 30,000 people die of opioid overdose every year in our country, business as usual.

It is far more dangerous to drive to the put-in of a river trip than it is to run rapids and camp under the stars and shit in the woods. We think nothing of whizzing along at 70 miles an hour in a lethal metal container in the company of hundreds of other lethal metal containers also going 70, but when a grizzly emerges a quarter mile upriver, shakes off, and disappears into the forest, minding its business, sirens go off internally.

Yeah, all well and good, but I’m suddenly really ready for everyone to get back from the hike.

Sawyer silhouetted against vastness.

The Mountain River is known for spectacular canyons, a half dozen of them. In the first couple of days the river runs through several unnamed, warm-up canyons, low walls and only a mile or two long, but still dramatic enough. The first real one opens with a snarling wave we manage to avoid, one boat at a time. The rock tilts almost straight up, tortured layers cut through by water, a clamp of bedrock rising sheer out of the riverbed. Water churns through, uneasy, blistering, jostling our boats, but nothing serious. We drift, milking the spot, taking pictures. Heady stuff.

Five days in we camp at a spot called Grizzly Meadows. The outfitters noted it as a good site, with some hiking nearby. We plan a layover day. It is an outwash plain full of braided, boulder-choked channels deposited by spring flooding. Only a trickle of water comes through at this time of year, but spring runoff must be a thing to behold. It is only after we’ve set tents up in the few available spots that Ruby notices a large pile of bear scat. Right in the middle of the berry-filled poop, a yellow whistle exactly like the ones on our life jackets.

“I’d kind of like to hear the story of how that whistle got there,” muses Sawyer. “Or maybe not.”

In the morning the weather turns gray and drizzly. We string up the green tarp that is quickly becoming the most valuable item of gear in the outfit, gather wood, cluster together around the grill. The kids have dubbed this trip, the Tour de Hot Drink. Most mornings we linger under the tarp, keep a pot of water boiling, down round after round of hot cocoa, coffee, tea.

Despite the misting drizzle, we stroll up the broad, rock-strewn valley. About a mile up we notice a tarp set on a low ridge overlooking the valley. Two guys in camo gear sit under the protecting eave, guns propped nearby. They wave us over.

It is a young guide from Calgary, probably 25 years old, and a client from Ft. Bridger, Wyoming. They flew in to a hunting lodge on a lake up a tributary, and then flew to a dirt strip nearby in a plane with ‘tundra tires’. They are staying at a cabin and hunting caribou, staking out the valley.

“I’d never camp where you are,” the guide says. “A lot of bear activity down there.”

The hunting party takes a bit of the edge off of our sense of wild seclusion. It starts to rain harder and we head back to camp, but after lunch the day clears and the kids decide to take on a hike to a ridge and several peaks up the valley. I am in camp-tender mode again.

They have only left camp a few minutes when I hear the sound of a rock rolling behind me. I have my back turned to the sound, busy disassembling a fishing rod. I turn. There, walking past less than 30 feet away, another grizzly bear. It moves fluidly over the ground, head swinging, shoulders working under a thick coat of long fur, paying no attention to me. Beyond the bear, I see my group up the valley, out of earshot but plainly in sight. The bear crosses the small tributary stream, keeps going. Strangely, I feel the need to announce myself, although I’m sure the bear knows I’m there.

“Hey bear!” I say.

The grizzly swings its head around, gives me a glance over its shoulder, but never pauses. I get the impression that it picks up the pace just a bit, but maybe I imagine that. There is no hurry in the bear’s movement, certainly no fear. It flows across space, liquid power, covering the ground it knows beyond any intimacy I might approach, following a path through home territory. When it gets to the far side of the outwash channel, maybe 100 yards away, it noses in the willows for a few seconds, then heaves up the dirt bank and vanishes into the underbrush. I see the bushes waving, and then nothing.

Only then do I look down and see that I’ve broken the fishing pole in my hands.

It is the fourth grizzly we’ve seen in five days. The attitude I adopt is that I am here, established in my spot, not bothering anyone. The bear is wandering through its territory, following its trails, not bothering me either. If the griz had wanted me, I’d have been an easy mark, probably never would have heard it come. We are each going about our business.

Okay, fine, but I turn my back to the river, scan the perimeter, build the fire, keep my weapons close. I probably read five pages an hour in my book, with how frequently I interrupt to check the valley. I have all afternoon to endure before I get some company.

It is a long vigil. Blessedly quiet and uninterrupted, but tense all the same. I spot the hikers now and then, on a steep scree slope, silhouetted on the ridge, coming back down. They take even longer than I expect, partly because they stop to pick blueberries on the return and troop back to camp all grins with a big bag of berries, blue-stained lips and plans for Dutch oven cobbler. They sober up some when I share my story, look around them, but the cobbler when it is dished up, hot and bubbly, is still delicious and the reassurance of company around the fire is profound, as primal as our species.

Days gather in our wake, we enter more canyons, skirt intimidating whitewater, run miles of fast current that require constant attention, take walks, sit under the tarp, heat pot after pot of water. The weather stays cool and changeable, more wintery than expected. More than once there is snow in the hills just above camp in the morning. Some of the tributary canyons we pass are stupendous in their own right. We walk up into them. In scale, they remind me of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone in Yellowstone National Park. Steep craggy walls, jagged cliffs, high perches for birds of prey. Caribou skitter away from us. Porcupine wander ponderously through the boulders. Wolf scat litters the game trails. Bear sightings drop off and we are grateful.

A rare sunny interlude enjoying the bug-free warmth.

At roughly the halfway point of the expedition, the Stone Knife River pours in, a tributary equal in size to the Mountain. It is milky green with glacial rock flour. The two flows are ribbons of contrast for miles, green and brown side by side, but eventually the green takes over and the current clears. More to the point, the river goes rampant with the doubling of volume.

“Whoa!” Everett says, when we peel away from shore below the confluence and the boats teeter precariously as they cross into the main flow. The river is instantly a force to reckon with, pushy with newfound power. The eddy lines are boat-tippers, the boils shove our canoes sideways, the waves and holes are twice the size we’ve been dealing with. We adjust, tiptoe down the first miles, feeling our way into the new dance, suddenly in the big leagues.

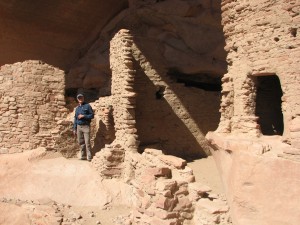

Along the way, as the weeks and miles pass, jewels of experience sparkle in the necklace of our watery route. Quinn performing a very credible Michael Jackson ‘moonwalk’ on the firm sand next to the canoes one morning; miles of fast river, clipping us along at 7 or 8 miles an hour, dodging boulders, riding tongues of current, slipping past the edge of holes, the shoreline whipping past; a lunch spot we climb to up a steep bank to gain a moonscape of glacial litter – erratic boulders, scraped bedrock, jagged pinnacles, depressions where we hide out of the bitter wind and the sun warms us so we strip down to shorts; a fountain-of-youth spring we scramble up to at the top of a cliff, bubbling clear and strong out of a rocky crevice; the bull caribou we watch in a swampy basin, agitated as a bull elk in full rut, rampaging through knee-high wetlands; Ruby fashioning ‘headset microphones’ out of driftwood twigs and performing on a gravel bar; the large black bear swimming the current as we come around a corner.

Exploring a side canyon, stunning in its own right.

We have decided that the merlin, that fast-winged dagger of predatory bird, is the trip symbol. We see them repeatedly, winging against canyon walls, hovering over an outwash stream, perched in the top of a snag. One morning, forty feet from our breakfast fire, a merlin lands on the sand. We watch, cereal bowls in hand, while the fierce bird of prey devours a songbird it has captured. It rips feathers, pulls the smaller bird apart, steadily swallows its meal down while we watch through binoculars. Finished, it flies to the top of a nearby spruce and begins to preen. We walk over to look at the carnage and there is nothing but a feather or two left.

Much of our attention has focused on the canyons that punctuate the valley. They are forbidding gateways of rock, looming high above the river, often with no good landings. In each there is some level of whitewater, some set of waves, or a ledge to avoid, or a wall the river slams into, undercutting the rock. Most of the worst water is avoidable, if you play it right and pay attention. Most of the canyons are more spectacular than dangerous. We pass roaring holes of whitewater at a respectful distance, ride the waves when we have to, slip past them when we can, steer clear of the walls.

Between canyons there are also moments. We take turns being the lead boat each day. The lead canoe makes the route choices, decides whether to stop and scout, points the way. Every boat is competent. Each team takes it seriously. Every choice is freighted with the knowledge of how remote and self-reliant we are.

One of a half dozen major canyons.

One morning Marypat and I are in the lead, and MP is in the stern. Early on, a few bends down from camp, the river makes a sharp corner, running past a steep rock wall. A set of intimidating standing waves mark the middle of the channel, with what looks like a strong eddy on the inside of the corner. We set up to ride the line between the worst of the waves and the upriver counter current of the eddy. But what we thought was calm water turns out to be a powerful boil blistering up next to the standing waves. As we enter the turn, the boil shoves our boat sideways. We slide across the river towards the main current and waves. Nothing we can do to fight the push of boiling river. The canoe hits the main current. Our gunwale is sucked forcefully down in the conflict and we are over in an instant.

The shock of cold current. I struggle to free myself from the spray deck. The dark water sucks around me. Finally I kick loose, but I am momentarily trapped under the boat, have to feel my way out from under. When I come to the surface, I see Marypat looking for me. We hang onto our paddles, start to swim the boat to shore. If we can make the eddy, it will help us. If we miss, we might be carried downstream a mile or more before we can make land. We stroke hard, hauling the boat behind us, breathing fast, encumbered by layers of clothing. We are lucky. The eddy brings us in. Meantime, the kids have landed above the rapid and are running toward us over the rocks.

“God dammit!” I throw my paddling gloves down.

Marypat looks at me, laughing. “You should have seen your face when you came up!”

“Yeah, it was a little desperate under there.”

“What did you lose?” Ruby asks.

“I think only my water bottle,” Marypat says. Ruby starts to jog downstream to look for it along the bank. “Don’t bother,” Marypat calls after her.

“Let’s get a fire going,” says Everett.

“You guys need to strip down, get warm clothes on,” says Sawyer.

The kids take over. It is gray and overcast, threatening rain. The wood is damp, but in short order they have flames, string a line to hang clothes on, help us get the wet, cloying layers off. Quinn gets the grill out, fills a pot with water, starts rummaging for hot drinks. Not that long ago I was carrying these guys on my shoulders, putting up with their shenanigans in canoes, cajoling them down the trail, cooking their food, changing their diapers, carrying their weight. It is a sweet circle to have come around, and a true relief to be the recipient of this payback.

All trip the kids have proven their worth, their skills, their judgment. Time and again, when I turn to do some task, I find that it has already been done. They are more than our equals now when it comes to strength and stamina, and they are proving our equals in making decisions and assessing dangers.

In the end we are delayed an hour or two. The rain holds off. Our clothes dry above the flames, we warm up with food and hot drinks. When we take to the boats again we are newly appreciative of the river’s power, and of the danger of the hidden boils that blister the current with muscular, unpredictable force.

Just another morning on the Tour d’ Hot Drink.

Canyon number five is the one to watch out for, we’ve heard. Canyons three and four had their adrenaline-laced moments – a ledge to avoid, a wave train to survive, a wall to miss. We have taken them in stride, careful but confident. The sketchy weather persists as we approach the gate of rock looming over a sharp right turn in the river. Gray, cool, drizzly. We are in full splash gear, paddling mitts, neoprene boots. Above the entrance to the fifth canyon a set of waves and a couple of ledges announce the challenge. We pull off, river left, to scout.

The train of waves is impressive, but along the left bank the current offers a slot of safety, as long as we can avoid the mid-river pull of water. Below the waves, as the river banks hard right, several ledges and holes lurk, spots we very much want to avoid. The trick is to sneak along shore to skirt the waves, but then make a power move across the main flow above the ledges to get to the right shore as we enter the gorge.

One canoe at a time we slip down along shore, back-paddling to tuck against the bank and stay well clear of the buck of waves. Marypat is nervous about the ‘ferry’ move we have to make across the river and wants to start as soon as possible. We turn the boat to face upstream, angle toward the far shore, power across. It is almost too early, too strong. The canoe is torqued in the last of the wave train, but we gain the far shore safely, wait for the other boats, turn back downstream.

The canyon rises sheer above the roiling river – holes, eddies, boils, water jostling for equilibrium, reacting to the constriction, to unseen, underwater obstacles. Each filament of river, each boulder, each nook in the shoreline sets up a fluid dynamic – changeable and tricky. At the same time the gorge is awesome, spectacular, dark and forbidding and exhilarating. Our three red boats slide through the vise of rock down the ribbon of water. At the exit the current slams hard into a sheer bedrock wall. It looks a lot like the river dynamics that capsized us a few days earlier – turbulent waves, a powerful eddy line, and treacherous upwelling boils blooming out of the depths.

Into the maw of another canyon on a chilly day.

We pull over above. Quinn walks down to have a look. She stands there at the edge of turbulence, hands tucked into her life vest for warmth. Quinn might as well be one of our kids. More than a cousin, she has been with us on dozens of trips, from the West Coast Trail on Vancouver Island to weeks in the Wind River Mountains in Wyoming. She has taken part in all the goofiness and triumph, pranks and danger that come with extended backcountry family time. She has grown up with us, and she has been a model of behavior, an absolute sweetheart.

When our kids were younger, and misbehaving, our admonishment to them would often be, “What would Quinn do?”

She comes back to the boats over the cobbles. “I think we should line down this,” she announces. “We might be able to get through, but it looks pretty scary.”

Without debate we all clamber out of the canoes and start walking them through the shallows. No one has an appetite for mishap, especially on a day with hypothermia conditions. And no one questions Quinn’s assessment.

At the end of the canyon we make camp. The mountainous terrain dramatically ends here. A steep wall of rock marks the edge of the rumpled landscape. Below it the river spreads and meanders another 50 miles to the confluence with the Mackenzie, coursing through one final canyon, a rib of rock, along the way. We have dawdled through the landscape to get here, but plan on a couple of long days through the bottomlands to finish out.

The tarp goes up, firewood is collected, flames coaxed out of damp wood, a pot of water put on to boil. It is a well-oiled routine by now – the knots that won’t slip on the tarp guylines, the collection of fire-starting tinder, the run for water, tents going up, boats tied to anchors, a pattern ingrained over the weeks, and a team that looks for what needs to be done and then does it. But the drizzly, cool weather is getting to us. Day after day of it.

In the morning it rains again. We get through breakfast under the tarp, and the sky begins to clear. Patches of blue open up, the sun shines through, we whoop in response. I let off a celebratory blast of the bear-deterrent air horn that makes everyone jump.

The sky clears, but by the time we load into the canoes for the day, the wind is howling.

“Be careful what you wish for,” I mutter, standing by the boats, looking at the spray whipping off the river.

All day wind hounds us. The river, here, is huge, braided, full of channels. We follow each other closely. If one boat takes a side channel, no telling when it would reconnect, and by the time it did, whether it would be ahead or behind the other canoes. The current continues strong and steady, but the headwind is dangerously tricky. It is powerful enough to tip a boat if you got broadside at the wrong moment and didn’t brace. Yes, the sky clears, the sun warms the land, but the wind is a torment. The recent rains wash in muddy torrents off the banks, turning the river brown and thick with sediment. What might have been a relaxing coast down miles of opening valley turns into a tense battle. Several times we consider stopping, but manage to inch our way past a bad reach and into a more protected section. Bit by bit we wind down the river and at the end, reach the final canyon, another rampant notch of rock, a final rib of resistance the river cuts through.

There is no whitewater to speak of, and part way through, a warm spring bubbles up. We decide to camp. The tarp goes up. The women go up to the spring for a tepid bath. Sawyer scampers up the slope to the final high ridge of the journey, let’s out a wild call, his tall silhouette against the sky.

On the final day the wind again blows a gale. The good news is that it has shifted direction to more of a quartering tailwind. We are able to make steady progress, but the canoes skitter across the current and there are precarious moments. Thunderheads loom in the sky, dark-bottomed bombs of storm. One of them comes our way. It’s hard to tell if it will hit us. On one bend we seem safely past. On the next, in the direct path of storm. And then, suddenly, it is looming directly overhead.

“Death-star alert!” calls Sawyer.

We drive the canoes hard into shore, haul them up into the willows, grab the tarp, race into a nearby alder thicket. As we snug the wild flapping nylon overhead, the storm hits. Winds lash the small trees, billow the tarp. Rain hits the flimsy roof of fabric like buckshot. We cower beneath, tightening lines, while the violence unleashes. It lasts maybe an hour. The dark sky, the loud crescendo of rain, the flailing bushes. It goes on long enough that I find myself lying down, napping on the pillow of my life jacket despite the cacophony. Then it is over. We peer out. The canoes are where we left them, the river courses past, the wind rages, but the dark-bottomed cloud moves on across the valley.

In the final miles before the Mountain joins the flow of the Mackenzie, the river takes a hairpin turn and wind battles us to a standstill. It is all we can do to claw our way against shore, inch by inch, up the long bend of current, the final salvo of challenge before this mighty flow we’ve paddled from its first narrow chuckle lets us go.

The Mountain is a major river at the end, but the Mackenzie is gargantuan. We paddle upstream from the confluence a quarter mile, find a place for our final camp. The water is so muddy we have to skim drinking water from settled puddles in the gravel. We find a pile of bear scat. Everett brings in a load of driftwood. Ruby starts the fire.

Sawyer retrieves the satellite emergency device we’ve carried along, loaded with contacts, capable of sending out an SOS in a dire emergency. He texts the bush flight dispatch center. KESSELHEIM PARTY AT CONFLUENCE. READY FOR MORNING PICKUP. Almost immediately he gets a response. ROGER. CAN YOU BE READY AT 9 AM? Sawyer responds, NO PROBLEM.

On schedule departure from the confluence.

True to their word, a few minutes after 9 a.m., the air blessedly calm, we hear the drone of approaching plane. The Turbo Twin Otter circles us, lands in the main current, taxis our way, backing in to the shallows. Fantastically, we load all three canoes and our entire outfit into the plane, and then climb aboard. Less then an hour later we are back at the float base, unloading, spreading gear out to dry, taking showers. The vortex of life begins to reel us back in – news of the world, phone calls, Quinn’s wedding updates, plans we’d forgotten about, wallets we haven’t seen in a month.

The next morning winter returns. It may be August, but here, a degree or two shy of the Arctic Circle, snow coats the nearby hills. Winds howl. At breakfast the outfitter gets word that scheduled air flights have all been cancelled and it will be another two days before we can get out.