CHAPTER 7: NOVEMBER – HULL PARTNER

It would be pushing it to say that I took the teaching job in northern Wisconsin, back in the late 70s, because of Grant Herman. There were other reasons. They flew me from Santa Fe, New Mexico to tiny Ashland, Wisconsin for a three-day interview at Northland College. Over those days I spent a fair amount of time with Grant. If I got the job he would be my partner running the Outdoor Education Department. The job was attractive, challenging, full of potential. It would add a lot to my resume. But the fact that Grant and I clicked immediately, that we found in each other a matching spark of enthusiasm and vision and style, had a lot to do with me finally saying yes, agreeing to leave the landscape of the West that I loved and a job I’d found pleasure in.

The contrast between urban, cosmopolitan Santa Fe and backwoods, off-the-radar Ashland was stunning. Back then, produce in the grocery stores along the southern shores of Lake Superior resembled something from a Hudson Bay outpost in northern Canada – some wizened potatoes, sprouting onions, misshapen carrots, wilted celery. Ashland was a town with more bars than churches, where patrons wore hunter-orange stocking caps all year round and hunched over Leinenkugels in dark caverns with stained-glass PBR lights dimly illuminating pool tables. Social life revolved around fish-fries on Friday nights and polka bands on Saturday.

Over the next three years, the town grew on me, the people I met, the fun to be had. I learned to polka, drank my share of long-neck Leinies, came to relish walleye, but it was the job that consumed me. Together, Grant and I made that program sing. The college, a small liberal arts school in the boonies of the upper Midwest, had come to an existential decision to distinguish itself by putting its curricular emphasis on the environment and the surrounding natural setting. Given that commitment, we were granted a lot of latitude.

We ran rock climbing trips to the Black Hills of South Dakota, whitewater boating courses in North Carolina, summer mountaineering expeditions to the San Juan Mountains of Colorado, spring trips to the canyons of Utah. We explored the northern boreal forest, the Boundary Waters, the coast of Lake Superior. We ran leadership seminars, winter skills expeditions, first aid classes, experiential education teaching workshops. On a campus with fewer than 700 students we had 150 majors. Heady stuff, and all consuming.

What I didn’t expect was to find a paddling partner in the bargain. I arrived in town for the school year with an Old Town canoe strapped to the top of my car, fresh from an expedition in northern Quebec. It wasn’t long before Grant and I were teaming up in boats of various stripes on the waters of the upper Midwest. The Brule, the Montreal, the St. Croix, the Wolf and Peshtigo, the expanse of Lake Superior – from intimate explorations of local estuaries to island-hopping through the Apostles. We paddled together in tandem kayaks, 36’ Montreal canoes, whitewater boats, flatwater canoes, expedition freighters. Between our course responsibilities we regularly escaped to the water and found that lovely chemistry of boating partnership, that dance with current, full of glory and mishap, adrenaline and comedy.

A lot of it was spontaneous. Some of it foolhardy. All of it charged with that youthful adventuring kinship so addicting and problematic.

One March we got it in our heads to respond to spring restlessness with a descent of the Brule River. Two bends in we came around a corner into a log jam with no chance to react, capsized, soaked our wool clothes. By the time we made the take-out we were blue with cold, and had given the still-warm-when-wet claim of wool clothing promoters a run for the money.

At the other end of the season, one November, we decided to run the Totogatic River in northern Wisconsin. The shuttle was a tad horrific, and by the time we reached the put-in, we’d devoted enough of the day to getting there that despite the dishearteningly low water level, we decided to go for it anyway. Mistake. The run was a top-to-bottom thicket of boulders we dinged and banged our way down, with a portage around a waterfall thrown in. Daylight was short. Light was waning and the end still a long ways off when I asked Grant nonchalantly whether he’d remembered matches. At that point I was assuming we’d be spending the night bivouacked under a white pine, cozied up around a fire. It would be chilly, uncomfortable, foodless, but doable. It would make for a good story.

“Damn!” Grant said. The fireside image went poof, and the urgency to get to the car gained a great deal of momentum.

It was twilight when we reached the ‘flowage’ reservoir that meant we were within reach of the take out. Our relief was short-lived, because a quarter mile onto the flat water a skim of ice slowed down our progress. We broke a wake, ice tinkling like broken glass before the bow. Then the skim thickened. We became an ice-breaker, ramming ahead, riding up on an elastic layer of ice, then breaking through. Then we were no longer breaking through, but the ice still wasn’t thick enough to get out and walk across. We backed up, shoved our way to the near shore, found a fisherman’s trail, and dragged the boat more than a mile through the woods as night fell and stars came out.

Or the Friday night fish-fry that turned into an all-nighter driving around the back roads of northern Wisconsin listening to the Allman Brothers at high volume, pub hopping, and deciding that a midnight descent of the sluggish White River would be in order. We picked up my canoe, drove to the base of the dam south of town and put in. The plan was to jog the five-mile shuttle back to the rig.

We set the canoe into the quiet flow. Got in. Went around the first bend. The frenetic energy of the night dissipated. The river was slow-moving all right, but also mined with frequent log jams and snags, overhanging brush, beaver dams. The night was impenetrable. We groped our way around corners blind, worked the boat through tangles of branches, pulled around obstacles, poked over low dams of sticks and mud. Beaver slapped the water next to the boat, startling as gunshots. We barely talked. It was oddly sacred, this space, at the same time that we kept giggling at ourselves. No one knew where we were. If something happened, we were on our own. The stretch to the next bridge was only a few miles, but it took us what felt like hours. By the time we saw the black stripe of state highway overhead we’d sobered up a good deal and now faced a five-mile run in the wee early morning hours.

About a mile down the pavement, huffing along, wearing stiff canvas pants and ragged tennies, a cop passed us and pulled over.

“You boys out for a little jog?” he asked.

We told him our story, at least the part of it featuring our midnight canoe jaunt.

“Hop in,” he said. “It’s a slow night. I’ll give you a ride.”

Even after I left Northland College and moved to Montana to be with Marypat and take the leap of faith into what I hoped would be a freelance writing career, I teamed up with Grant on boating expeditions. The summer after I left Ashland, we spent a month on the Seal River and Hudson Bay in northern Manitoba. It was Marypat’s first northern expedition, her first real time in a canoe, and the start of our northern era together. A few years later we joined Grant on a month-long kayak traverse of the entire Canadian coastline of Lake Superior. And a few years after that we met for a week in September in the Boundary Waters of northern Minnesota.

Boats and water have defined our relationship, but it had been a long time since we’d paddled together. Maybe twenty-five years. Both of our lives had moved on. We kept in touch, visited once in a while when driving through, but contact was sporadic. On a whim I texted Grant about joining me on a November river trip, briefly explained my year of trips theme. I suggested the San Juan River in southern Utah. November would be pushing the season, but we’d have it to ourselves and it is an awesome run through panoramic Monument Valley, a nice follow up to October’s Grays and Desolation journey, farther north. I figured it was a long shot.

“Interesting,” Grant texted back, almost immediately. “I’ve got some details to deal with, but maybe I can pull it off.”

I went ahead and got the permit. In November permits are a piece of cake, required a whopping fee of $6, and whether or not Grant joined me could wait. Grant’s ‘details’ were complicated. He had moved with his wife to the Olympic Peninsula, a gobsmacking leap, given that he’d lived in the north woods of Wisconsin for more than 40 years, and they were extricating themselves from a sea-kayaking operation they’d run near Bayfield, Wisconsin. It involved a neighboring Indian tribe with boundary issues, trying to sell the business, and some major construction. I knew how those things went. I thought the likelihood of having his company was south of 50/50.

So it was a pleasant surprise when he called to say he thought he could pull it off. Still, I didn’t count on it until Grant bought a plane ticket to Bozeman. We would spend a day gearing up together, another day driving down to Utah, and get in the canoe for a week. I was eager for all of it – the time dinking with gear, the hours of driving and catch up, and most of all, that moment when we would step into a loaded open canoe together and match up paddle strokes.

Some friendships take no time at all to rekindle. After a separation, even years long, the same warmth fires up, the familiar repartee, the ease granted by deep trust and history. It’s like that with Grant, from the moment we meet at the baggage claim and haul his whopping duffle off of the carousel, through the next day’s checklist minutia of river shoes, tie-down straps, dry bags. A dinner together with Marypat and an early departure for a long day’s drive south, red canoe strapped overhead.

We drop easily into conversation, interspersed with silence, watching the countryside morph from Yellowstone Plateau with its thickets of lodgepole pine and mountain ranges edging toward winter, to the spreading aridity south of Salt Lake City . . . Price . . . Green River. Past our turn to the Green, the month before, and down to Moab, where we stop at a Mexican joint for dinner.

It is well past dark when we pull into the campsite at Sand Island boat launch outside of Bluff. We are the only ones there. We put up tents by the light of car headlights. Around us, the shoulder of sandstone cliff, the scent of nearby flowing water, the dusty earth, shadowy clumps of sage.

We stand around for a minute in the cold dark. A fat moon breasts the horizon. “I’m really glad you came, Grant,” I say. “I think you’ll like this river. But I’m going to bed.”

In the chilly dawn, after a bagel and cup of coffee, we drop off our keys at the shuttle joint, top up the gas tank, fuss around at the boat ramp with the pile of gear. It’s a tight fit in the boat. I indulged with a full-sized cooler, and we have the obligatory porta-potty, a 7-gallon water jug, the various dry bags full of gear. The canoe hull is maxed out and Grant has to wedge his feet around the water jug in the bow. The San Juan is on the low end of flow, around 700 cfs, a silty green ribbon schussing by. There are no river rangers to check in with, only one other car in the parking lot. Before we leave we stand in front of a massive panel of petroglyphs near the launch, a mural of indecipherable symbols and story lines that runs the length of a football field on a low cliff.

And then, that moment all of this has led up to, when we step into the canoe together.

“I’ll take the left,” I say. It is my preferred side to paddle on in the stern. We push gently off from shore. Our paddles hit the water. The canoe enters the current. All so familiar, so rich.

Silence is a pretty comfortable state for us. Riding in a car, in the boat or at a camp, we can sit and share space without cluttering it up with meaningless chit-chat. By the same token, when we talk, it is without a lot of pretense. I reveal my decision to quit drinking, for example. “I kept trying to rationalize being a moderate social drinker,” I say to Grant. “Eventually I had to admit that I couldn’t do it.”

Grant takes it in. A good deal of our social interaction over the years has been fueled by beer. Part of my anxiety over quitting drinking has had to do with my lack of faith that I can be as socially engaged and entertaining without the lubrication of alcohol. Taken on face value that seems pretty pathetic, but there it is, lurking under the surface. On some level I know that insecurity is ridiculous. Inebriation certainly doesn’t make me more eloquent or funny or insightful. It just fools me into feeling that way. Yes, it can make for some boisterous fun, general silliness, less inhibited interaction, but shouldn’t I be able to manage some level of fun without it? For Grant it seems to make no difference at all. He is the same friend he’s always been. It’s me suffering the angst.

The San Juan runs through a collage of cultures and artifacts, past and present, like a historical kaleidoscope. Within the first couple of miles, the highway 191 bridge crosses the river, funneling traffic south. Also within the first hour or two on the water, the canoe slides past a series of ‘toehold routes’ snaking up sandstone cliffs, precarious footholds chiseled out of rock that I populate with loincloth-clad natives making their daily commutes to and from the river. Petroglyphs punctuate the riverside cliffs, some visible from the water, others up washes, symbols from another paradigm. There are ruins of old trading posts, foundations eroding slowly into the landscape, carvings left on rock by passing Mormons, haphazard junk left behind by miners, an historic wagon road snaking up the rough ridge overlooking Comb Wash.

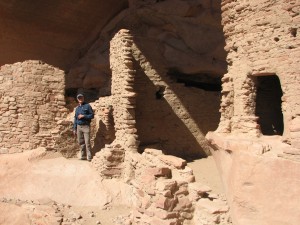

We pull in and walk through a half mile of scrub to get to River House Ruin, a substantial Pueblo set of structures built under the eave of overhanging cliff 1,000 years ago, give or take a few hundred years – granaries, sleeping rooms, corn-grinding stones, much of it relatively intact. I imagine the care taken to choose a site that was defensible, protected, angled to get the most out of the morning sun and afternoon shade, safe from flood. I imagine people sitting in the morning summer dawn, greeting the day, or ducking through a low doorway into a sleeping room, or grinding cornmeal against worn stone, or diverting river water to crops.

The human ebb and flow along the San Juan goes back at least as far as the Clovis culture, some 12,000 years ago – big game hunters who may have been responsible for the extinction of megafauna in the region, from sabre tooth cats to gigantic sloths. They were followed by the Basketmaker culture, and then the Pueblo people. While that summarizes what we surmise was the progression of indigenous cultures in the area, there are long gaps in the record, and much is cloaked in mystery. It’s worth remembering, too, that the rendering of indigenous history by western archaeologists may have little in common with the native understanding of their origins and migrations through time. For them, the Bering Strait land bridge migration is a theory fomented by a foreign culture. Their origin stories involve Spider Woman and Sipapu emergences. Their cultures continue corn pollen ceremonies, fertility rites, and embrace a worldview in which animals and plants, weather and rocks possess sentience, hold equal standing with us in the cosmological order of things. Currently, the Navajo reservation borders much of the river, and that side of the river is only accessible to the public through a bureaucratic maze of fees and permits.

In recent centuries the river valley has drawn an influx of Mormons, surges of fur trapping, mining, and oil exploration, and the first river runners exploiting the recreational potential of float trips with whitewater thrills. As with most large western rivers, the San Juan is impounded behind a dam at Navajo Reservoir, near Farmington, NM, and flows are largely controlled by dam releases. Periodic flash floods and the largely undammed Animas River are the other natural forces that can dramatically alter river levels.

And it can be dramatic. The first time I paddled the San Juan, in the late 1970s, I was in an aluminum canoe, back in the days before river permits, and early in the evolution of my paddling expertise. We’d camped above Eight-Foot Rapid and were waiting for our partners before launching at the top of the whitewater. I wasn’t paying much attention, but noticed that I repeatedly had to pull the canoe up higher to keep it from floating off. Then I looked at the river, which had suddenly thickened with sediment, and was carrying down sticks and logs and assorted flotsam. By the time our companions got organized, the river had risen half a foot and the rapid had morphed from a minor drop to a formidable challenge, all because of an upstream flashflood.

Through all of this, the march of human habitation and the overlay of exploitative vandalism, the river has coursed its patient way downhill toward the confluence with the Colorado, and on to the sea. The San Juan runs on the geologic clock, slowly writhing back and forth across the canyon floor in snaking meanders, grinding its way grain by grain through the layers of cross-bedded sandstone, limestone and shales, entrenching oxbow bends and goosenecks, deepening the chasm, one season raging with the erosive power of flood, and the next peacefully chuckling along. Flash floods, boulders rolling downhill, banks sloughing away, vegetation coming and going, species winking out. The river nods along through the millennia, water molecules coalescing and responding to gravity in the simplest of equations.

Grant and I drop into an easy paddling rhythm, much as we picked up the thread of our friendship when we met at the airport. The low volume requires picking our way through thin stretches of river, finding the deepest thread. Grant sees where I’m heading, throws in corrective strokes in the bow to miss rocks or hit a ‘v’ of channel. The teamwork is satisfying, reinforcing, dynamic.

Maybe the most seminal chapter in our paddling history together was initiated by the purchase of a used C-2 in Green Bay, Wisconsin. To the uninitiated, a C-2 is a class of boat that looks like a tandem kayak. It is a fully decked boat with two cockpits, but in a C-2 the hull contours have more in common with a canoe than a kayak, the paddlers kneel rather than sit, and they use single-blade canoe paddles rather than a double-blade kayak paddle. C-2s come in a wide spectrum of designs, from high-volume, fairly roomy craft to surfboard thin hulls that act like sports cars in current, as long as the paddlers know how to drive.

On the way back from Green Bay we put the boat in a stretch of river along the state highway and gave it a spin. In less than 200 yards we capsized and had to swim ignobly to shore, towing our new toy. Paddling that thing involved a learning curve, and it came at the price of excruciating pain.

The hull was so tight that we were literally kneeling with our butts sitting on our heels. A small pedestal of foam served as a minimal seat, but our legs were numb most of the time and we were forced to shore about every 45 minutes where we dragged the paraplegic lower halves of our bodies out of the hull and writhed around on the ground regaining feeling. Then we’d squeeze back in and get the payoff of another 45 minutes of wind-in-the-hair exultation.

One of our best moments came on the Brule River, at high water, when we decided to turn the boat upstream to surf in a wave train. Grant was in the bow. We paddled onto the crest of the wave, where the recirculating current held the boat in place while we balanced and kept our position. Then the bow began to plane down in the water, submerging. Grant went in to his waist. About then I realized that the stern was also interacting with the next wave downstream, and that I too was getting submerged. Slowly the boat went down. Grant went armpit deep. Then I was up to my neck in the current, barely able to keep my paddle braced on the river surface. We realized then that we were both kneeling on the bedrock bottom of the river channel in our boat, with current roiling around us.

Whatever dynamic we’d initiated kept us there for a few seconds, vibrating in the flow, with no idea what was coming next. Then, slowly, the hull released from the bottom, began to surf its way back to the surface, until we reemerged into the air like a breaching submarine. We were alone. No one witnessed the event. There is no You Tube video. But what else can you do, alone together on the river when something so stupendous takes place, but laugh out loud and forget the fact that you haven’t felt the lower half of your body for the last thirty minutes? God, what a boat!

On the San Juan our teamwork is more pedestrian, but no less satisfying, and a lot more comfortable. We pass the only other boater we see all week on Day 2, a young guy in an inflatable boat who is taking out above Mexican Hat. The days are pleasant, about as warm as you could wish for in November. Nights are chilly and long, a reminder of the ebbing season of light. Most mornings there is a skim of ice on the water bucket. We are in no rush. Camps are set with an eye toward morning sun, and while we wait, we cradle mugs of coffee and let the day come up around us.

At the end of Day 3 the canoe rests on shore beneath high cliffs just past the Goosenecks, a series of remarkable entrenched meanders the river has eroded some 2,500 feet deep through layers of sedimentary rock. It is an iconic spot in the desert southwest. If you’ve paged through a coffee table picture book featuring the region, the likelihood is that you’ve seen an aerial shot of the dramatic goosenecks. We plan a rest day here to hike the Honaker Trail. Camp is set in a protected pocket of sand, surrounded by large boulders and a couple of well-placed juniper.

The challenge of November is daylight. The weather is as benign as we could hope for – little wind, pleasant days, clear nights. But just after an early dinner the lights go out and cold creeps in. We build fires in our fire pan at several camps, but even then the sleeping bag beckons and we are in the tents early, reading and writing by headlamp, staying warm.

To say that the Honaker Trail looks improbable is like saying sailing Cape Horn is no walk in the park. From the river the cliffs rise sheer to the skyline, layer after thick layer of sediment in a series of ramparts that defy navigation. We pack a lunch and some water, set out after a leisurely breakfast. Some bighorn sheep watch us from the water’s edge across the river. How they travel the cliffy terrain is a wonder, but they are far more up to the challenge than we are.

A rock cairn marks the start of the trail. We turn up. The trail was initiated by Augustus Honaker in 1894. He and those that followed kept tweaking and engineering the route over the following decade as an approach to the river and what they hoped would be lucrative gold mining prospects in the sands and gravel of the canyon depths. Like so many endeavors of that period of frontier history, the effort was horrific. Whether it’s crossing craggy mountain passes in covered wagons, hollowing canoes out of cottonwood trees and descending rapid-filled rivers, or simply hewing a homestead out of the bush, the labor, the ambition, the brute physical toll, is unimaginable.

More to the point, what seems unimaginable at the start is that this thread of a path will actually wind its way up 2,500 feet to the canyon rim. We take it on faith. The trail climbs to a narrow ledge at the top of one of the rock layers, and then contours down canyon for a long ways until a break in the next layer above affords a way through. At the top of that, another shelf we double back on and follow gradually up to the next eroded spot to climb through. The grade of the trail is surprisingly moderate, as wide as a sidewalk. Still, a few feet to the side, the cliff falls away. We climb through the layers. We see the speck of red canoe on the beach, our tents in the bower of juniper, the next bend in the canyon.

What Grant hasn’t said much about is that as he has aged, he’s developed a more and more acute fear of exposure. When I told him about the trail he mumbled something about fear of heights, but seemed game.

Grant is a veteran outdoor educator, a guy for whom edgy adventure and sports are a way of life. But now he stays close behind me, keeps his gaze focused on my boots, doesn’t dare look to the side. He is uncharacteristically quiet, fighting his internal terror. I stick to a slow, steady pace, check in with him periodically. “I’m okay,” he keeps saying, while his body posture plainly says he is anything but okay.

When we stop for a break half way up he climbs above the trail onto a flatter spot of ground, visibly leans away from the abyss, even though the edge is dozens of feet away. I walk out onto an exposed shelf of rock called Horn Point and ask Grant to take my picture, arms outstretched in the airy expanse. “You couldn’t pay me enough to do that! I could barely stand to take the picture,” he says, handing me the camera.

The trail defies the topography. It is surprisingly moderate, well graded. Even the corners where it climbs up to the next ledge are engineered with buttressed walls of boulders. But for a couple of spots to scramble through, you could wheel a cart along it. The fact that Honaker, and the miners who followed, found the route, and then put in the stupendous effort to grade and fortify the trail, is remarkable. It has been true of all the ruins we’ve seen – cabins on top of cliffs overlooking an oxbow bend in the river, piping systems, roads, just the transport of heavy cables and equipment, is hard to comprehend.

In the case of this trail, this endeavor, it was all for naught. The gold prospectors had hoped to cash in on in the canyon below turned out to be little more than trace flakes in the ‘flour’ of sediment washed downstream from a source far upriver. Within a few decades the miners gave up hope, leaving behind the legacy of this whacky route to the rim with its sweeping views.

Grant is visibly relieved when we gain the plateau. We eat lunch looking over the shimmering buttes and pinnacles of Monument Valley, getting the aerial view of the goosenecks we wound our way through the day before. Down in the bottom we appreciated the geology, knew we were paddling through a wonder, but we couldn’t comprehend the scope of it. It was like wandering the warren of back alleys in New York City without the understanding of the wider reality of a maze full of back alleys radiating out for miles in every direction. From the top we get it. The San Juan has etched its way down through the layers of sediment, ‘entrenching’ its course, trapping itself in the vise of rock, sawing back and forth in a ribbon of channel sometimes only a quarter mile from the next bend down as the raven flies, but separated by sheer walls thousands of feet high.

Away from the lip of the chasm, the landscape looks relatively flat, spreading to the horizon. Imagine beetling along under the desert sky as part of a wagon train in the mid 1800s and abruptly pulling up at the edge of this. And the San Juan is only one of many natural obstacles that confronted early pioneers and explorers. Coming up with Plan Bs was a daily fact of travel.

Grant is no more comfortable going down. He keeps his gaze focused on my feet, goes quiet. When we sit for a rest, he backs away as far as possible from the edge, leans back against solid ground. The bighorn sheep are still across the river when we tromp back to camp. Grant returns to his usual self, seems equal parts relieved to be done and proud that he pulled it off.

For the next two days our focus is the river and our teamwork in the canoe. Brilliant days. The tributary canyons, spectacular as they are, remain a sideshow to the dance between boat and current and paddles. We talk our way through minor riffles, stop to scout a couple of heavier drops, discuss strategy, run our lines, team up in the way we have over the decades. It all comes back.

“Remember that day on the Montreal?” I ask, at one point. Grant just laughs and nods.

The Montreal is a short river that runs along the border between northern Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. It is dam-controlled. Much of the time it is an unrunnable, boulder-choked channel, but when the dam releases a pulse of water, boaters all over the area drop whatever they’re doing, call in sick, load up boats and head for the put-in. We were no exception. One spring day the dam release alert went out among paddlers and we dropped everything, loaded up Grant’s whitewater canoe on his beater Datsun truck, threw in bikes for the shuttle, and drove over.

The river was high and pushy, full on. We took up our positions, secured ourselves like racecar drivers for the ride, and pushed off from shore. The intensity went from 0 to 10 the instant we entered the current. Our paddles dug into the water in power strokes. From the get go the boat dodged and wove through rocky stretches. The yellow canoe plunged over ledges, threaded the needle between rocks, spun into tight eddies. For long sections we were breathing as hard as we would on a run. We talked some, shouted directions here and there, but there was no time for discussion. Mostly we read off of each other, complemented strokes, saw or, more likely, felt what the other person was doing and reacted.

Once in a while we found a larger eddy along shore to turn into and take a rest, straighten our legs, get feeling back in our hands, bail some water. It went on for hours, just the two of us charging down robust current, paddling right at the edge of our abilities, occasionally letting out a yell or laughing out loud, but mostly saying nothing to jinx the moment.

That day everything clicked. Magic. Like a sports team in perfect coordination, a gymnast in the groove, dancers moving in flawless choreography, an artist under the spell. It was the kind of day that shines bright through the decades. Back home that night I couldn’t sleep for the replay tape of the day running in loops across the mental stage. And here, thirty years on, we both have it on instant recall.

Occasionally we turn into shore, get out, stretch our legs, have a look around – John’s Canyon, Slickhorn, Grand Gulch. Mostly we relish the time in the boat. At night we build fires, watch the first stars and planets come out, stay up until the cold drives us to the tents. In the mornings the light seeps back into the day, warmth comes, feeble but reassuring. Two cups of coffee, maybe three. Easy conversation, roll things up, stuff the canoe, and pick it up again.

My sister-in-law’s father had a period in his life during which he and some old college buddies would take long road trips every year. They covered ground – the eastern seaboard, the desert southwest, the Pacific coast, southern Canada. Once they drove, pretty much non-stop, from Arizona to Niagara Falls. They arrived in the scenic parking lot from which they could see the frothing cascade of water going over the brink. They all looked at it for a few minutes, glanced around at the tourist crowds, then one of them said, “Okay, where should we go for lunch?” It was all about what was happening in the car, not about the destination, not about the passing scenery. Being in the boat with Grant is something like that.

For the final 20 miles, from around Slickhorn Canyon to the take-out at Clay Hills Crossing, the San Juan is clogged with sediment. It is the unfortunate legacy of Glen Canyon Dam, far downstream along the Colorado. The dam, built in the early 1960s, backed up Lake Powell in a gigantic, misplaced evaporation pond. The Colorado, arriving headlong out of Cataract Canyon, fueled by inertia built from Wyoming and Colorado and northern Utah, carrying an unguessable tonnage of sand, hits the slack water and drops its load. The result is that the tributary rivers back up too, building up sand and dirt and mud in deep, unnatural layers. Almost 30 miles upstream from the confluence with the Colorado, the San Juan is choked with it. The channel spreads out wide, sheets over the sand in a shallow, slow, braided flow.

From above it’s easy to pick out the deeper, green-hued channels. On the river it’s impossible to tell, and it doesn’t conform to the usual laws of current. Normally you can count on deeper water on the outside of bends, for example. Not so here. The deepest flow might be right down the middle through a sandbar lurking two inches below the surface. Mile after mile we feel our way along, seeking the hints of current, the greener water, the fickle pattern. When we run aground we push off through quicksand in search of deeper water. Back and forth we weave across the valley.

Our final night we camp at Steer Gulch, a few miles above the take-out. It is the last minor canyon before Lake Powell. It is quiet there with the river murmuring past. In the gloaming, as I set up my tent, a canyon wren calls from the rock ledges above camp. It is the first canyon wren we’ve heard all week – that stirring, happy call of the desert. It comes again while I stand there, tent stake in hand. The birdlife has been sparse this trip. Some Canada geese, a few flycatchers, a couple of raptors, small flocks of songbirds. Things are settled in for the season. Migrations are done. Life is hunkered down.

In the morning, early, as we pack up, the wren calls again, a descending cascade of music ringing against canyon walls. Both Grant and I look up, catch each other’s gaze, lean into the fading echo of song in the dusky light of dawn.