Twenty miles south of Meeteetse, Wyoming, going seventy miles an hour, I top a rise and see the hitchhiker. Middle of nowhere. Empty two-lane. Gray, fall day – clouds clipping along, sandstone bluffs pocked with juniper, a raven sailing the updrafts, a skiff of snow in the hollows. A full backpack leans against his thigh. Thumb high. Nice smile. Some road wear, but presentable enough. Reminds me of me – forty years ago. I haven’t picked up a hitchhiker in decades. All of this ticks across the mental screen, then he is in my rear view mirror.

In October my mother died. It happened suddenly, at home, without violence. She was there, then not.

Nothing prepares you for losing your mother. It’s like having children. No test drive available.

Ever since, I have been yo-yoing the 14 hours back and forth from Montana to spend time with dad, who is alone now in the house he shared with Chelsea for a quarter-century. He is not ready to leave. He may never be. My sense is that, much as he appreciates visitors, the condolences, the demonstrations of community, he is also keen for his own company, and for the tart solitude of grief. When he says goodbye, and turns back inside, it is with relief.

My cousin happened to be visiting on the day mom died. He said that Chelsea had been disoriented for a day or so, had dizzy spells, lost track of things. He sat with her after breakfast the last morning of her life. The night before she had woken my dad and asked him to take her to the kitchen so she could reorient herself to the house. That morning there were birds at the feeder outside. Sun pooled in the room. She had come to the point where so much about life was burdensome. She hated her mind, her looks, her fragile skin, the pills in weekly trays, her dependence. The nagging about using her cane, the fact that we took the car keys from her. She kept apologizing for her halting speech, her search for simple words. But she was lucid.

“I believe there is good in everyone,” she said to my cousin. “I have always believed that.”

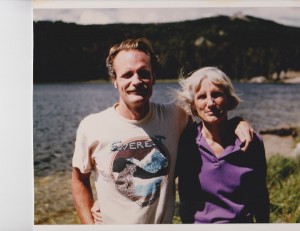

Chelsea was famous for picking up hitchhikers, even into her 70s. An old lady, alone in her car, on some desolate Wyoming road, she would pull over and pick disheveled strangers up. Drove us crazy to think of her doing that. More than that, she would take people in, inviting them home for a meal, letting them stay a few days, giving them odd jobs, paying them wages worthy of the oil patch. Did they take advantage? Sure, some of them, sometimes.

“So what?” she would say.

The hitchhiker is still there in the rear view, his silhouette tiny, shimmering slightly in the windy distance. No cars in sight. I find myself downshifting, looking for a wide spot on the shoulder, then swinging an abrupt arc across the highway, heading back.

I clear junk off of the passenger seat while he wrestles his pack into the back. We shake hands, start talking. He is from Montreal, a college student. He was tired of endless school, decided to take six months and travel until his money ran out. He bought a plane ticket to Seattle and started hitching from there, stringing together a web of geographic highlights he’d researched online. The usual suspects – Yellowstone National Park, Devil’s Tower, the Black Hills, but also some off-the-radar nuggets even I wasn’t familiar with.

“Hell’s Half Acre,” he says, when I ask where he’s going. “It’s a little park halfway between Shoshoni and Casper that sounds really cool.”

“I can get you to Shoshoni,” I say.

We talk about hitchhiking. I tell him I used to hitch when I was his age, that it was commonplace back in the 60s and 70s. People did it all the time. Now it seems more desperate, the people generally pretty sketchy.

“I want to keep the tradition alive,” he says.

He speaks with a slight French accent. I look over at him. I think what I would be feeling if he were my son saying that. Honestly, I don’t know, but I like him a great deal for the sentiment. And I think back to the gritty roads I waited on at his age, with the heft of my pack resting against my thigh, with the frontier of pavement and unscripted encounters gaping ahead across Arizona, or California, or Pennsylvania.

He is unabashedly excited at the sight of pronghorn. I pull over so he can get a photo to send home. Half a dozen graze in the sagebrush across a line of fence. In the distance, the swell of peaks, the piles of cloud, the roll of space. “I told them I was seeing antelope,” he says, “but I don’t know if they believed me.”

Fifteen years before my mother died, she wrote her epitaph.

It was an exercise at a writing retreat. She had been thinking about energy. When her own mother was dying, Chelsea stayed with her so she could be at home. In the last weeks, her mother traveled. You never knew where she’d come up. France in the 30s. New Orleans. Puerto Rico. Mid conversation with someone on 42nd Street, New York.

One day my mother asked her about God, what she made of it all. She was quiet a long time, barely breathing. She had come to the point where she hardly ate or drank. Already half gone. Hard to say whether she had heard, whether she was sleeping, where she’d slipped off to. Chelsea was used to waiting.

Then, abruptly, her mother said, “It’s all energy. That’s what I think about God. Energy.”

In the years since, Chelsea often referred to that notion, a web of nebulous, unfathomable, but quite real forces mingling and transforming and intersecting throughout the universe. And so, her epitaph, scrawled on a white page of lined paper.

“Nothing is lost, only transformed.

Look for me in your memories,

In the generations past and to come.

See me in the blowing grasses,

The flowing rivers,

The spring mud and winter snows.

See me in the sage and the grazing antelope.

Nothing is lost, only transformed.”

We slow down for Thermopolis, then enter Wind River Canyon. My passenger, whose name I never learn, takes movies through the windshield. The canyon walls rise in craggy ramparts. The river, low now, feels through the bends.

I know he is thinking about what’s next, when I leave him again on the side of the road. What time of day it is, how much light he has, whether he’ll have to walk out of town to find a good spot, what he’ll have for dinner. Hitchhiking requires uncommon faith, the belief that needs will be met, that you will survive the bad spots and accept the good ones.

Shoshoni is visible from ten miles out. I think about rides I had, a generation back. Drunks in ramshackle vehicles that needed oil more often than gas. A semi hauling 65,000 pounds of popcorn. A band of hippies in a day-glow micro bus in Glacier National Park. I remember the day-to-day of it, the yearning, the edge of mishap sheer and close, the sweet and heady loneliness.

In her last morning my mother kept talking, apologizing as she searched for words, but clear enough. My cousin sat with her.

“Inside everyone there is a pure jewel of light,” she said. “Everyone is born with that. Our job, through the years, is to keep that light clear. Things happen to obscure and hide it. Scars and wounds cover it up. Our work is to keep it clear so that it shines out on the world.”

She got up then, my cousin told me. She made her way to the couch where she lay down to prop up her swollen legs. She rested against pillows.

“Five minutes later, she was gone,” he said.

We stop in Shoshoni. I turn toward Casper, drive to the edge of town, drop him off at a rest area. It’s a good spot. We shake hands. He heads for the bathroom before resuming his journey. I wish him luck. He waves.

So I turn around, head back west, toward my father, who is waiting for me in the house still so full of her. And all the way to him it is full of her. In the wind burring across the reservoir. In the late sun firing the Wind River Range. In the fleet antelope standing watchful in the twilight, preparing for night.